Identité volée | Stolen identity

Quand les Canadiens français revendiquent une identité autochtone | When French Canadians claim an Indigenous identity

À lire en français dans ONFR+ et en anglais dans La Tourtière | Read in French in ONFR+ and in English in La Tourtière

Ancré dans le récit de Marie Bernard, mon aïeule Algonquine, je vous présente mon nouveau texte pour ONFR+, une exploration de mon identité culturelle à moi. Un énorme merci au chercheur Darryl Leroux et à ma soeur Émilie pour leur générosité et leur engagement envers la vérité et la réconciliation.

Anchored in the story of Marie Bernard, my Algonquian ancestress, here is my latest for ONFR+, an exploration of my own cultural identity. Sincere thanks to researcher Darryl Leroux and my sister Émilie for their generosity and their commitment to truth and reconciliation.

Stolen identity

When French Canadians claim an Indigenous identity

Her name was Marie Bernard.

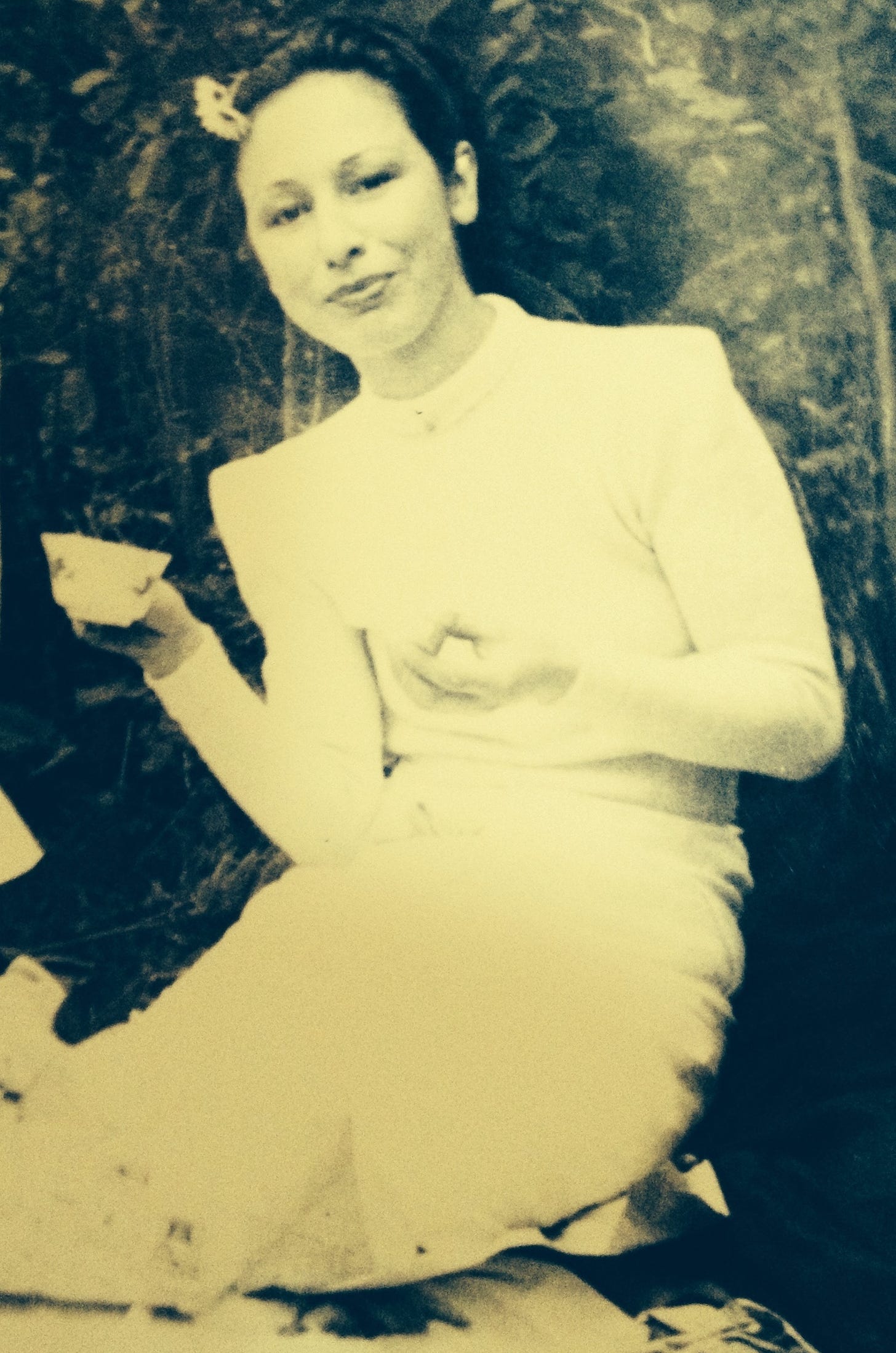

My proverbial nokomis. A grandmother and Algonquin ancestress.

“Marie Bernard probably came from Rivière Rouge in Quebec,” explains Émilie Bourgeault-Tassé. “We found her in the 1871 and 1881 censuses – but while she was first identified as Indigenous, she was also later identified as French Canadian.”

Émilie is my soeurette – my younger sister. A woman with whom I share a curious last name. And a sacred fire for justice, truth and reconciliation. Who, like me, wants to smash the patriarchy in a quest for a decolonial, fair and equitable world.

And who, like me, is sometimes ascribed an identity that is métissée (mixed).

French Canadian and Franco-Ontarian, she and I are the heiresses of Eugène Bourgeault, nephew to great grand uncles who, according to family lore, fought for Louis Riel and the Métis in Manitoba.

Of “ma tante” Philamène, an adoptive Algonquin and French Canadian auntie who would grace my grandfather’s life – and that of his beloved, our grandmother Isabelle Bourgeault, née Patry.

Marie Bernard’s great-granddaughter.

“According to the family legend, Isabelle Bourgeault was proud of her roots, even at a time when people hid their Indigenous ancestors,” says Émilie, who has been working with First Nations, Inuit and Métis communities gathered in the Robinson Huron Treaty territory (1850) in N’Swakamok (Sudbury) for over a decade.

“Marie Bernard evoked enormous curiosity for me and for the whole family – but we know almost nothing of her life. We know that she was Catholic and a mother of many children. But did she speak Algonquin? Did she attend ceremonies? What was her attachment to her culture? To the land? It’s all very mysterious.»

As Émilie explored our Algonquin genealogy, she also confronted the rise of the “pretendian”, those who claim an Indigenous cultural identity, often based on a distant Indigenous ancestor, or on French Canadian myths and oral tradition.

“Everyone was mixed race – that’s what myth and family lore in French Canada tells us,” explains researcher Darryl Leroux. “Today, people identify as Indigenous because of these stories.”

A French Canadian and Franco-Ontarian, Leroux is originally from Sudbury. A professor at the School of Sociological and Anthropological Studies at the University of Ottawa, he is the author of Distorted Descent: White Claims to Indigenous Identity, which explores this mythology and the self-indigenization of French Canadians who are blurring the lines between whiteness and indigeneity.

This “mixed-race chimera” has serious repercussions: from New Brunswick to Ontario, approximately 300,000 Franco-descendants define themselves as Indigenous, a movement that comes at our own peril in an era of important cultural conversations and denunciations around false cultural identity claims.

“Thirteen Indigenous women married French men before 1670 – but they have about 10 million descendants today in Canada, and 2 to 3 million in the United States, perhaps a little more. These are millions of people who could claim to be Indigenous on the basis of a single ancestor,” explains Leroux.

According to Leroux, false claims to Indigenous identity are a reversal of the truth and reconciliation movement. The financial damage – ranging from positions and places reserved for research and study grants – is considerable. Ibid legal infringements by organizations claiming treaty rights, sometimes even at odds with genuine Indigenous aspirations.

The usurpation of the hard-earned rights of First Nations, Inuit and Métis people over the years is a setback for the aspirations for justice, truth and reconciliation, explains Leroux.

“There are many institutions – such as universities – that repeat beautiful words to give themselves a certain cultural, social, political capital, to place themselves among those who want to fight inequality,” he begins. “And when they are told, you have replaced real Indigenous people with white people, these institutions abdicate their responsibilities, so that non-Indigenous people have control over reconciliation on campuses, in governments, et cetera.”

“It’s as if all of a sudden Doug Ford and his entire gang call themselves Franco-Ontarians – and then they’re the ones who are going to speak for the community because they’ve learned our history,” he says. “It sheds light on symbolism, the lack of materiality, a willingness to really do something meaningful about reconciliation.”

Indigenous identity, he says, is not simply a matter of blood or ancestry, but a matter of belonging to kinship practices that are specific to different nations and territories.

This is a vision shared by my sister Émilie.

“Indigenous ancestry does not give us hunting or harvesting rights, treaty rights, or a voice in the aspirations and claims of Indigenous peoples,” she says.

Nevertheless, adds Émilie, French Canadians must honour their Indigenous ancestry by participating in the cultural and linguistic development of First Nations, Inuit and Métis peoples and by joining forces in their struggle and their quest for justice.

“Marie Bernard is sacred to me – my daughter is her seventh generation. She opens me to an extraordinary world, but she also belongs to a whole constellation of ancestors that I must also claim,” she says.

“I honour my nokomis with my practice of truth and reconciliation, in the hope of becoming myself an ancestor who will be the pride of future generations.”

Well said ! Same applies in Northern Maine. Acadians arrived in Native American land in the 1700's. The written article depicts a very similar situation as ours. I, myself might be considered "métissée". My main interest, however, is wanting justice and equity.