Frog Power

Cinquante ans de fête et de fight à La Nuit sur l'étang | Fifty Years of Fête and Fight at La Nuit sur l'étang

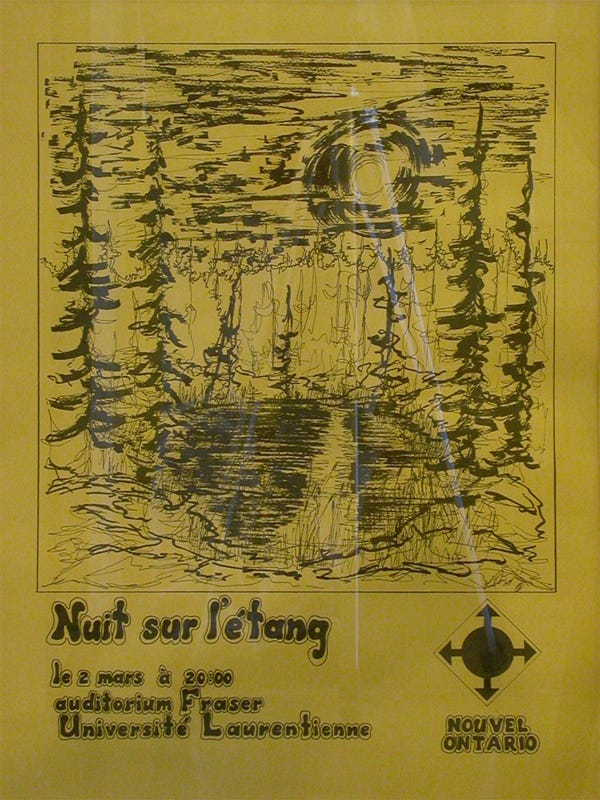

On était 1973 – époque du «Frog Power» au Pays du Gros Cinq Cenne. Ici, à Sudbury se dessinaient les reliefs du Nouvel-Ontario, une géographie imaginée, cette «terre de pierre, de forêts et de froid». Un bout de pays reculé où la jeunesse franco-ontarienne réclamait sa voix. Libre. Et forte.

«On est tannés d’être sous la domination de la majorité», se souvient le journaliste et rédacteur d’opinions Réjean Grenier. «On veut un autre type de bilinguisme. Un bilinguisme où nous sommes égaux».

En 1973, les étudiants et étudiantes à l’échelle planétaire montent aux barricades, les poings levés, afin de manifester contre l’injustice où qu'elle soit – y compris à l’Université Laurentienne, au cœur du Nouvel-Ontario.

Lisez la suite en français dans ONFR+

It was 1973, a shining era of francophone “Frog Power” in the Nickel City. Across Sudbury was etched an imaginary northern geography, le Nouvel-Ontario, a “terre de pierre, de forêts et de froid – land of rock, forest and cold,” remote country in the north where Franco-Ontarian youth were claiming their voice. Free and strong.

“We are tired of being under the domination of the majority,” remembers journalist and opinion writer Réjean Grenier. “We want another type of bilingualism. A bilingualism where we are equal.”

In 1973, students from around the world mobilised, fists raised to protest injustice wherever they saw it – including at Laurentian University, in the heart of le Nouvel-Ontario. As a retort to the marginalisation of the French fact at the university, idealist and brazen youth – including a young Grenier, then a francophone student leader, organised Congrès Franco-Parole which, among other things, proposed to hand over the decision-making power over university education in French to Franco-Ontarians.

“There’s going to be a lot of talk and good ideas,” reportedly said Fernand Dorais, the charismatic Jesuit, professor and co-organiser of Congrès Franco-Parole. “But I don’t see any fun.”

These young intrépides had to do more than organise. They had to dream, too. They needed un parté. A “campfire.” A night in the swompe.

An Iconic Nuit

With Gaston Tremblay, young writer and author of the illustrious Molière Go Home manifesto, Grenier conceived and organised Une Nuit sur l'étang (A Night on the Pond) – which would soon become La Nuit sur l'étang – opening under the stars at Laurentian University’s Fraser Auditorium on March 17, 1973.

If the soirée “was of questionable quality,” remembered eminent artist Robert Paquette, set against the recycled set of the fabled Franco-Sudburian play Moé j’viens du Nord s’tie – I’m from the north, goddam, “a half-transparent tulle shimmering with red and blue,” as Tremblay wrote, the curtain rose on an iconic Nuit.

“A roll of timpani tears the silence,” wrote graduate student Marie-Hélène Pichette of that memorable first Nuit in 1973. “The beat intensifies; the signal is given. The participants, until then seated in the room, rush the stage. On behalf of all Nouvel-Ontario artists, they seize la scène: une Nuit sur l’étang is born.”

There was music. Song. Poetry. Theatre. And even macramé. Young CANO on the verge of superstardom in Canadian music. André Paiement, a shooting star who would make our remote pays d’hiver a northern light in the firmament sang that night. So did his sister, Rachel Paiement, who took to the stage for the first time ever, her voice like a snowstorm sweeping through pine during a winter night. Marcel Aymar was also there, his own soft Acadian intonations crashing like ocean waves on the young crowd. And countless others who would leave a legacy in le Nouvel-Ontario and beyond.

"The fête birthed us"

Celebrated until dawn in Sudbury over the course of decades, La Nuit became a rite of passage from which we would emerge drunk and dizzied with music, poetry, vibe and franco-fraternity, brimming with fête and fight, amazed by the sun rising on le roc, ready to build le Nouvel-Ontario and shine our light on the world.

"The fête birthed us," Dorais once wrote. "Seeing ourselves and speaking ourselves through performance fulfils us in the recognition of a wounded fraternity."

“Viens chanter l'histoire de ta vie. Viens partager ce que tu es aujourd'hui – Come sing the story of your life. Come share what you are today,” sang Aymar in Viens nous voir, a toune that would emerge as the evening’s opening hymn a decade later, a song that “tells the story of the depths of solitude but also of a community gathered in a great reunion,” a rite giving voice to our “wounded fraternity.”

Joy – and résistance

The “collective madness of a people in party,” as André Paiement once described it, La Nuit allowed us to recognize ourselves and speak ourselves through poetry, theatre, music, and celebration. In the last light of winter, this “veillée d'hiver chaude comme une nuit d'été – a warm winter evening like a summer night,” drew us from our cocoon of ice and invisibility, offering as resistance an expression of collective joy.

Fifty years later, La Nuit persists as a fête where, to borrow from poet Robert Dickson, “we stubborn, subterranean and solidaires, release our raucous and rocky cries to the four winds of the possible future”.